Surplus Dairy Calves

- 26 Jan 2022

- 0 Comments

Due to improved animal welfare, new regulations and an overall push in the industry, the next topic will not be a concern to all, but it is still an area for improvement.

After watching the ADSA virtual conference, I thought I would expand on Dr. Dave Renaud (University of Guelph) and his webinar on surplus calves in the dairy industry.

In the EU including the UK about 11 million male dairy calves were produced by the industry in 2020. A surplus calf is defined as a calf that is not needed to produce milk.

Surplus calves pose a significant reputational risk in the dairy industry, and I am a big believer that no one should be able to question our capabilities or the passion for our livestock and we should all be following the same standards to highlight this.

What are the challenges ?

Within any industry there is likely to be challenges. The first challenge to be addressed would be high levels of mortality and morbidity. It was reported 2-15% of these surplus calves' face mortality with 90% receiving a treatment.

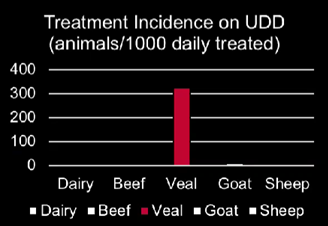

Second challenge, due to high levels of disease would be the increased use of antimicrobials. A paper from the Netherlands showing the veal/dairy beef industry being the highest users. Source: Catry et al. 2016; Santman-Berands et al. 2014.

Finally, compromised housing and nutrition, often fed lower quantity/quality colostrum, therefore inadequate immunity increasing health challenges.

Where do we start to address these challenges?

The simplest way is to follow this road map, to note where there are increased stressors and how it may have an impact on disease resilience.

Dairy farm → Transportation → Auction/Collection centre/Calf rearer → Transportation → Calf rearer/Finishing unit.

Following this process will help improve the care throughout the production chain.

The dairy farmer can have the greatest impact on the future success of the calf, the high standards of protocols for dairy heifer calves are equally important for the male/beef calves.

Better colostrum management will improve successful passive immunity, hugely important with improving health and stressors the calves are faced with. Studies have shown that 30% of male dairy calves have failed passive transfer.

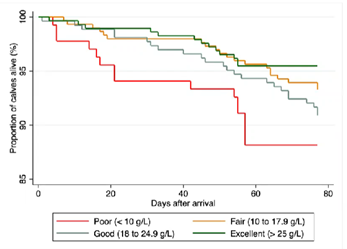

Blood samples of 1000 calves were taken, determined the serum level of IgG and associated the IgG levels and the subsequent risk of mortality. The poorly transferred calves had a greater risk of mortality within the 80 days they were under observation.

Other challenges would be the low bodyweight and young age that calves leave the dairy farm. Bodyweight is an important predictor as a future risk to mortality on the rearing unit.

Likewise light to moderate calves are more likely to have to receive a treatment when to compared to moderate and heavy calves. (Light <43kg, light – moderate 43-47kg. moderate 47-50kg and heavy >50kg) Source: Goetz et al, 2021.

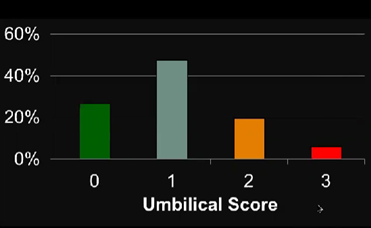

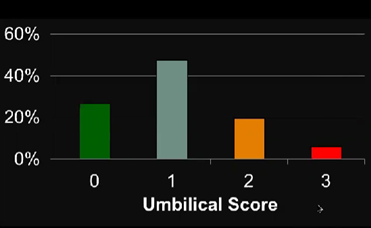

Another study of 5000 calves arriving to a veal facility showed a high level of disease arriving onto the rearing unit, suggesting the calves should have remained on the dairy farm. Score 3 showed an umbilical infection, 5% of these calves had an infection.

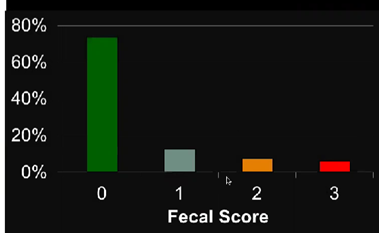

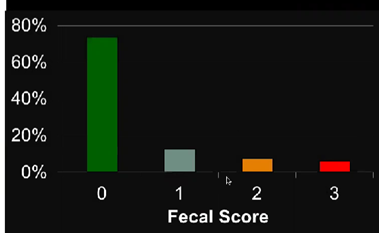

Fig 4. shows calves that experienced diarrhoea, scores 2 and 3 indicate 13% of calves had diarrhoea onto facility. Results show that only 40% of calves having no abnormalities when arriving to the unit.

Source: Goetz et al, 2021, Scott et al., 2019, Renaud et al, 2018

A final study was on transportation (travel time a lot longer than we have in the UK, but a major factor to consider with the impact it has on these young calves) 100 calves were randomly assigned and to a travel group of 6 hours, 12 hours, and 16 hours.

They were then monitored for 14 days on the veal facility. Findings show that calves transported for 16 hours had a greater proportion of days with diarrhoea compared to calves transported 6 hours. The 16-hour calves experienced an extra day with scour.

Secondly the 12- and 16-hour calves had higher levels of fat mobilization compared to the 6-hour calves. Finally, weight change, all groups had a long time to recover to pre transport weight, which increases cost of production.

As an industry we are going to be supply more beef from the dairy sector. The first weeks of life are vital to ensure these animals are going to perform throughout the supply chain.

We need to look to improve health, reducing the use of antimicrobials and reducing mortality and morbidity %. We need to investigate further stressors like transport and dehorning and how we can minimise the impact these have.

Summary

As I have said before, we need to focus on producing feed efficient animals, that will have a reduce days on farm and provide a consistent product to consumers whilst maintaining the best animal welfare standards and outlook on the industry.

- Adequate colostrum is vital for the calves to perform

- Age and size can have a significant impact on disease resilience, we may face regulatory changes with keeping calves longer to meet bodyweight requirements

- Minimise transport stress – provide a milk feed before transport

- Calf rearing facilities to maintain high standards from dairy unit

- Mitigate the reputational risk by following high welfare, gold standards

Fig.1. Source: Catry et al. 2016; Santman-Berands et al. 2014.

Fig.2. Source: Goetz et al, 2021

Fig.3. Source: Goetz et al, 2021, Scott et al., 2019, Renaud et al, 2018

Fig.4. Source: Goetz et al, 2021, Scott et al., 2019, Renaud et al, 2018