What you need to be mindful of when feeding whole milk to calves

-

- 4 Jun 2024

- 0 Comments

“Whole milk” could be:

· Colostral milk

· Transition milk

· High SCC milk

· Antibiotic milk

· Mastitis milk

· Raw or pasteurised bulk milk

· Raw or pasteurised waste milk

Depending on the farm’s definition of whole milk, the constituents can vary greatly. When aiming for a consistent nutrient supply for calves, it is important we try to minimize variation on the ration provided to them.

What are the positives of feeding whole milk?

It is close to nature (when fed at high volumes) and therefore is highly digestible and energy dense (high in fat). Whole milk also contains bioactive ingredients - which we are unsure of their true value of when it come to calf health and performance. Whole milk can also provide an outlet for unsaleable milk, therefore can be quite cost effective. In terms of labour, it can also be quite simple as there is little infrastructure needed in terms of warm water provision and mixing ratios of powder.

What are the challenges to feeding whole milk?

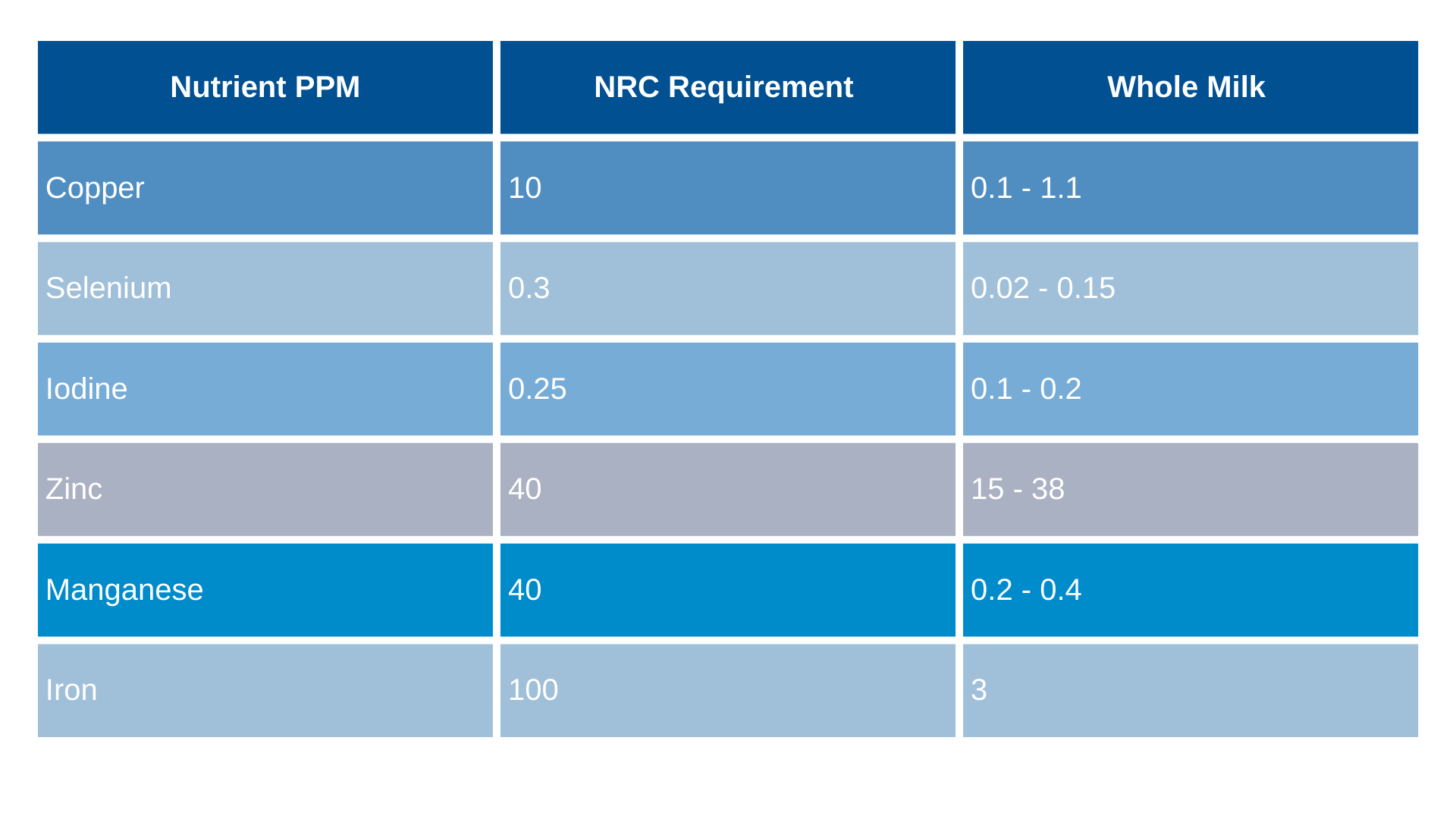

There is a greater risk of disease transmission (Johnes, TB ect) and may contain potential harmful pathogens (particularly raw waste milk) alongside this risk is also the risk of antibiotic traces in whole milk (colostral milk, transition milk or antibiotic milk) which can lead to resistance. Whole milk can also be low is vitamins and trace elements especially. Table 1 outlines the comparison between NRC calf requirement and Whole Milk.

Depending on the system there can also be seasonal and daily fluctuations in the constituents of whole milk, therefore not providing consistency to the calf. It can also be constricting to staff if they are tied waiting for milk from the parlour.

Milk powder offers consistency and minimises the risk of disease, whilst providing the calves with their recommended nutritional requirements.